Education at COP30: What the Outcomes Mean for Safe and Resilient Schools

Mahmuda Akter, Global Climate Hub Network Coordinator at Plan International and GADRRRES member

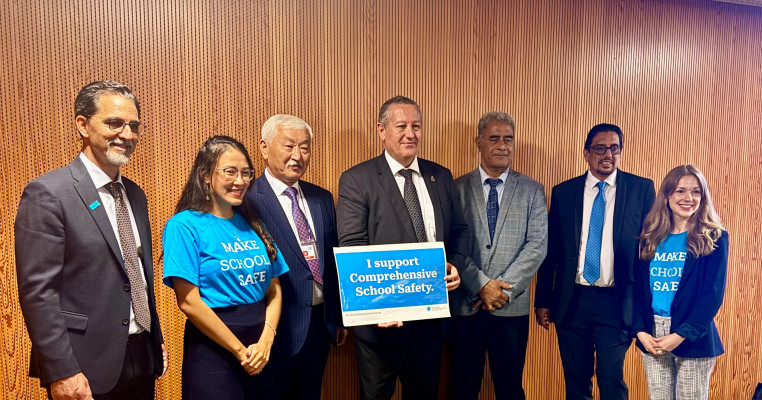

At COP30 in Belém, governments arrived with the ambition that this would be the “Implementation COP.” Yet for education and school safety, the negotiated outcomes only partially met expectations.

While political leaders repeatedly referenced children, youth, and future generations during the High-Level Segment, the final texts under the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), the Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE) agenda, and the capacity-building framework did not fully translate this rhetoric into operational commitments.

As El Salvador reminded the plenary, “The most profound changes do not begin in the large forums, but in the classrooms.”

While COP30 outcomes did not embed education nor school safety as structural components of climate action, the Conference did deliver important political signals that reinforce the urgency of climate-resilient education systems, creating clear opportunities for education stakeholders engagement in the years ahead.

Education in the Negotiated Texts

ACE & Capacity-Building (SB Decisions)

The ACE and capacity-building decisions reaffirm Party commitments to strengthen knowledge, skills, and public participation. However, they introduce no new finance mechanisms, and implementation remains voluntary and nationally driven. Children and youth continue to be recognised broadly as stakeholders, but the decisions do not provide pathways for their formal participation, leadership, or accountability. This leaves a significant gap: education systems are not being prioritised within global climate governance, despite their central role in risk reduction and community resilience.

Adaptation (GGA): Education Recognised Politically, Omitted in Final Texts

One of COP30’s headline achievements was the adoption of the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) framework and its 59 indicators. However, none of these indicators explicitly reference education, school safety, or learning continuity - despite these being essential pillars of resilience for children and communities.

This omission stands in contrast to the High-Level Segment, where leaders from Spain, St. Lucia, The Gambia, Nepal, and Seychelles emphasised that protecting children and adolescents requires protecting schools and education systems. The Gambia captured the urgency: “We cannot fail our children. We cannot fail our youth. We cannot fail our future.”

While the indicators include areas relevant for school safety such as WASH, health (including mental health and psychosocial support (MPHSS)), social protection, early warning systems, and monitoring and learning systems, they fall short of integrating the education sector into climate adaptation planning. These elements are essential, but without comprehensive approaches to education, the GGA lacks a core component of social resilience.

Just Transition Work Programme (JTWP)

Through the Belém Action Mechanism (BAM), COP30’s Just Transition decision embeds essential rights-based foundations - participation, equity, labour rights, and Indigenous Peoples’ rights, as well as skills development. However, the final text does not explicitly reference education systems or youth skills, leaving a gap in how countries will support learning, training, and resilience-building through their just transition pathways.

This omission also weakens the connection between just transition planning and the education sector’s needs, such as youth-focused green skills, climate-resilient TVET systems, teacher capacity development, anticipatory action in schools, and education-sector inclusion in labour and social protection planning.

Technology Mechanism & Capacity Building

While the Technology Mechanism and the Capacity-Building Initiative for Transparency (CBIT) confirm the importance of technical training, institutional strengthening, and South–South cooperation, they do not reference school-based climate resilience, curriculum reform, climate-competent teacher training, or technology access for learning continuity. These gaps limit the ability of education systems to meaningfully integrate climate risk management and innovation into teaching, learning, and school operations.

Where COP30 Leaves Us

Across the final decisions, COP30 acknowledged the moral imperative to protect children and youth, yet did not embed education or school safety within the implementation frameworks. As the Marshall Islands cautioned during the High-Level Segment, “Negotiators must become navigators.”

For the education sector, this means navigating fragmented climate governance structures to secure protection for learners and ensure that schools and education systems can withstand and adapt to escalating climate impacts, even when global climate frameworks fall short.

Opportunities for GADRRRES

Despite COP30’s gaps, the years ahead offer meaningful avenues for the education sector to shape global, regional, and national action on climate-resilient education. GADRRRES stands ready to play a leading role in these efforts.

Influencing GGA Indicator Refinement

Between Bonn 2026 and COP32, GADRRRES will seek to play a critical role in advocating for the integration of education-relevant indicators - including learning continuity, child protection, school safety, and MHPSS in education settings - into future GGA refinements and national implementation strategies.

Strengthening the Just Transition Mechanism

As the Belém Action Mechanism is operationalised under CMA8, GADRRRES will seek to advocate for greater emphasis on youth skills, green workforce development, climate-competent teacher training, and resilient school infrastructure as core elements of just transition frameworks.

Supporting ACE Implementation

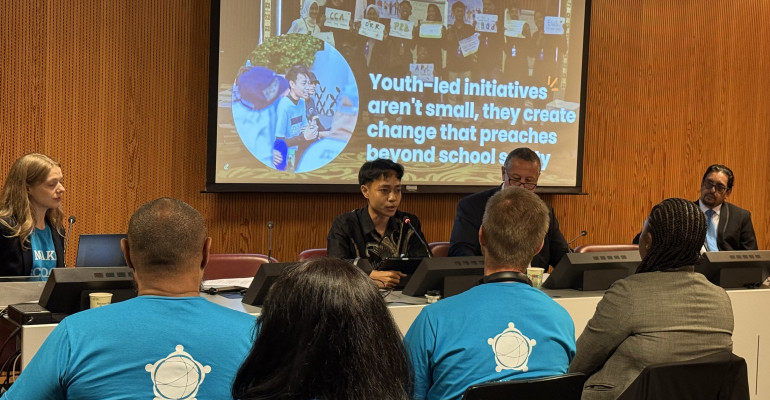

GADRRRES will seek to support countries to strengthen ACE implementation, including developing national climate education action plans, integrating climate content into curricula, and empowering students through mechanisms that support youth-led climate leadership and local action.

Highlighting Education in Loss & Damage

As the Loss and Damage Fund becomes operational, GADRRRES will seek to emphasise the importance of addressing school damage, loss of learning, psychosocial impacts on children, and gender-responsive support for adolescent girls. These elements must be part of financial allocation criteria to ensure that losses in the education sector are not overlooked.

The Path Forward: Making Education Central to Climate-Resilient Development

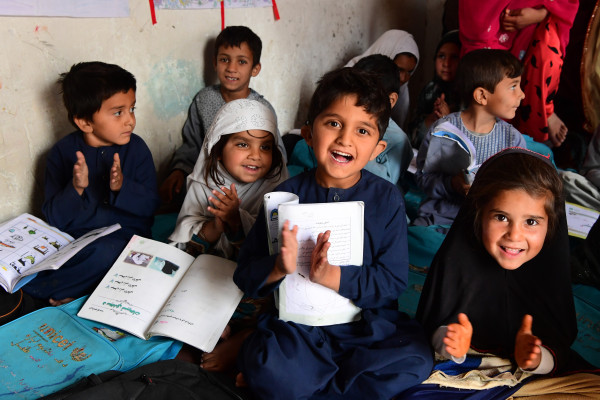

COP30 affirmed the urgency of protecting children and youth, but left education systems largely outside the formal architecture of climate action. Yet schools continue to be damaged by extreme weather, learning is disrupted, and teachers and students are on the frontlines of crises, but these realities were not fully reflected in the negotiated outcomes.

For GADRRRES, this gap is not a setback - it is a clear signal of where action is needed next. The coming years offer critical openings to ensure that education is recognised not as a secondary concern, but as a foundational pillar of climate resilience, disaster risk reduction, and community wellbeing.

By actively shaping upcoming negotiation cycles, supporting ACE implementation, strengthening adaptation metrics, and elevating education within climate finance and loss and damage discussions, GADRRRES can help define a future where climate action protects not only the planet, but also the learning, safety, and dignity of every child.

Now is the moment for the global education and DRR community to step forward. We have the evidence, the tools, and the partnerships. What’s needed is collective action, louder advocacy, and stronger collaboration.

GADRRRES invites governments, civil society, youth leaders, and education actors to join us in making education central to climate-resilient development, for today’s learners and for generations to come.